The world was just coming to terms with the "ua-parser-js" npm library hijacking incident, and Sonatype's discovery of crypto-mining malware from last week, when we found a bigger, and spookier, issue just in time for Halloween.

Could threat actors abuse open source ecosystems, like npm, PyPI, and Rubygems, to deploy ransomware? This crucial question was raised for the first time because of our most recent discovery of malicious npm packages:

-

Noblox.js-proxy

-

Noblox.js-proxies

The answer was an unequivocal yes. Let me go into the full details. These typosquatting packages mimic noblox.js, a popular Roblox game API wrapper that exists on npm as both a standalone package, along with legitimate variants such as "noblox.js-proxied" (ending in 'd' not 's'). Both of these have been tracked under sonatype-2021-1526 in our security research data.

Noblox.js is an open source JavaScript API for the popular game Roblox. Users commonly use this library, downloaded over 700,000 times to date, to create in-game scripts that interact with the Roblox website. Since we discovered the two typosquats so quickly, they both had minimal impact. Noblox.js-proxy seeing 281 total downloads, and Noblox.js-proxies seeing 106 total downloads, but it's clear what type of scale the threat actors were hoping for going after such a popular component.

But, the developers behind malicious typosquats noblox.js-proxy and noblox.js-proxies have implemented some extra unwanted functionalities — trojans, ransomware, and even a spooky surprise.

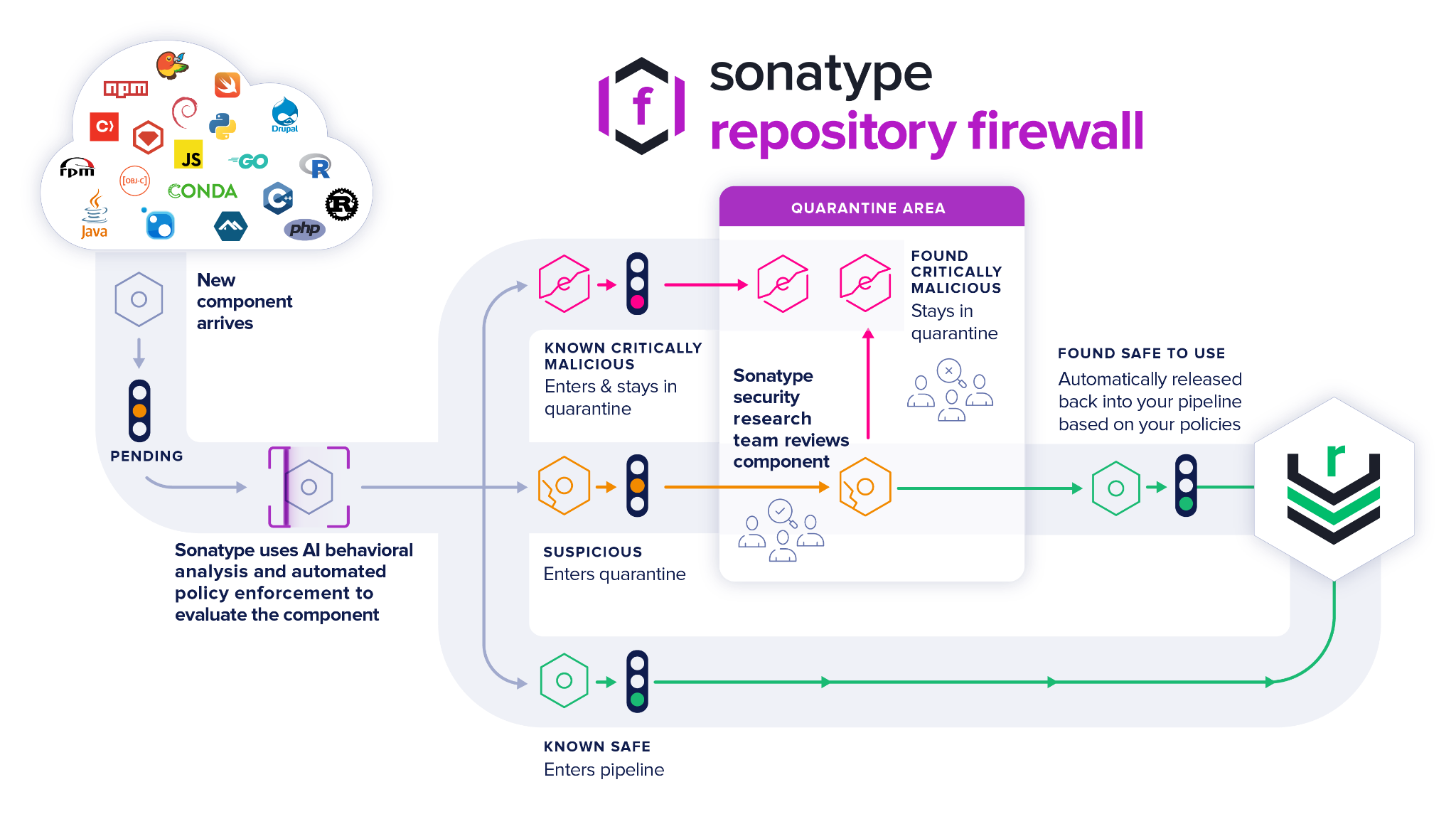

While Sonatype's automated malware detection system flagged Noblox.js-proxy, our security research team also came across noblox.js-proxies. This highlights the importance of combining automation and human research in protecting our open source ecosystems - and why we at Sonatype have not only built the system to find the issues, but also employed an army of researchers to confirm them.

Note, due to many similarities between noblox.js-proxy and noblox.js-proxies, along with the fact that they are uploaded by the same threat actor ('DarkDev' or 'DarkDev1'), we have referred to the packages interchangeably, and any references to behavior of noblox.js-proxy are also largely representative of the latter’s behavior.

Typosquats Display the Noblox's README Page on npm

At first glance, the packages look legitimate, as the npm page shows the README for the official Noblox package.

The first release of noblox.js-proxy, version 1.0.0, looks completely normal. It contains functional code, correct definitions, and a benign post-install script. But starting with 1.0.1, we noticed some obfuscated text within what used to be an inoffensive postinstall.js file. It's fairly common for threat actors to place the malicious code within the manifest file, package.json file, and even more commonly these days, within the pre and post-install scripts defined in the manifest file. And that's also the case here.

The package.json file launches the "postinstall.js," which contains a suspicious line of code:

While legitimate reasons can be legitimate reasons projects minimize their code or even obfuscate it, a seemingly random piece of obfuscated code in the middle of plain readable functions is an immediate red flag. Let's focus on that.

Obfuscated, Minified JavaScript Drops a Cryptic Batch Script

Besides just highlighting what the threat actor did in this instance, I wanted to share a little about how security researchers investigate these types of findings. Here are some of what I went through to truly identify whether this was malicious.

After a while of trying to deobfuscate this code and get something readable out of it, I came to the conclusion that I need to work on my obfuscation, encoding/decoding skills. However, I'm decent with dynamic analysis, so I decided to try my luck there.

Interestingly, on launching the malicious package in an Ubuntu VM I had handy, I got an error message stating `cmd.exe /c setup.bat` couldn’t be run. Looking at the directory where I executed the malware, I now also saw a setup.bat file. Both the 'cmd.exe' reference and the dropped Batch file instantly indicate the malware targets Windows users.

I noticed, the Batch file was heavily obfuscated, which was odd. Then, upon looking more closely, it appeared encoded, with what looked like Chinese characters. At first, I even put them through a translator to make something out of it. Then, some google-fu came to the rescue.

Turns out this was a UTF-16 file, and all I needed was to save it as such and tell my text editor how I wanted to view it (thanks to the StackOverflow post that resolved the mystery).

Next, I opened the batch script in my favorite text editor and took a look. Once again obfuscated, or was it?

The result of re-opening the file as UTF-16 was a lot better, but I still couldn't make much out of it. There were some URLs buried in cleartext there that were readable and led to malicious binaries, but I wanted to better understand this.

Some more google-fu and I read about something called variable expansion. This is a process of simply replacing a variable enclosed in % or ! with some value. I knew the URLs I saw had to be prefixed with 'https,' so I started replacing some values with what I knew should be there, then added some automation to get an awesome result.

After a successful round of variable expansion, the Batch script became legible:

Batch Script Alters Windows Registry, Drops Trojans, and Ransomware

And then, everything started to become clearer. The Batch script first attempts some Windows User Account Control (UAC) bypasses via fodhelper.exe, a trusted Windows binary that facilitates 'Features on Demand.' This is followed by the use of PowerShell download ‘cradles’ to grab some malicious executables.

At this stage, the following malicious executables are downloaded from Discord's CDN server:

-

exclude.bat

Going through them and performing some dynamic analysis, in great part assisted by the awesome any.run sandbox, we can start to piece together what this malware is actually doing.

The one-liner batch script, exclude.bat runs first, and attempts to turn off antivirus agents. To avoid detection, it adds the C:\ directory, which is the root, to the Windows Defender exclusions list.

Next up is legion.exe, which drops multiple files, including a stealer.exe, and performs registry changes to avoid detection. But, the main functionality of this executable is to steal Discord tokens and stored browser and system credentials. To achieve persistence, legion.exe also copies itself as the Microsoft Update Manager.

Run Away! Or... Ran-Some-Where

Now it's 000.exe's turn. This is a .NET executable, meaning we can use ILSpy or dnSpy to roughly reconstruct the source code. At first, I noticed some interesting operations with keyboard hooks, then I came across some more dropped files:

000.exe is dropping even more files: a Text file, a Batch script, rich-text (RTF) documents, an EXE, and finally an MP4 video, as shown above. Here is where it gets spooky.

Text.txt is just a file containing the string "UR NEXT." Windl.bat attempts to set the Windows user account name to "UR NEXT," drop the malicious RTF file and execute rniw.exe. The rniw executable attempts to exhaust system resources by repeatedly popping up alert boxes with the message "Run away" and pinging 1.1.1.1 non-stop.

But that's not all. To ambient the threats correctly, the threat actors even played a video that gave me goosebumps.

Finally, tunamor.exe is spun up, which I thought was funny given that amor is Spanish for 'love' but there is absolutely no love in here. This executable is flagged by VirusTotal as a Remote Access Trojan (RAT), possibly TAIDOOR. Taking a look at the executable itself, we can see this isn't just a RAT, this is ransomware, and it's likely our bad actors are after a payday.

Below is the ransom note generated by tunamor.exe:

While unconfirmed, the ransom note looks identical to the ones seen in MBRLocker variants, generated using publicly available tools released on YouTube and Discord. A report released by BleepingComputer last year stated that MBRLocker variants were likely used as part of 'pranks' to be played on people.

To sum it all up, we have a malicious typosquatting package with the main goal of stealing tokens, credentials, installing Trojans, and infecting the victim's system with ransomware — all of this with some fun but spooky videos and notes along the way.

Oddly enough, the threat actor also posted copies of these malicious packages [1, 2] to GitHub, but pushed an additional commit to remove the malicious code:

At the time of our analysis on October 20, 2021, the malicious package "noblox.js-proxy" was already taken down by npm. However, a second package "noblox.js-proxies" emerged shortly and was discovered by Sonatype yesterday, October 26, 2021. We promptly reported the package to npm and the npm security team removed it in less than an hour of our report.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

Files checksum (SHA-1):

legion.exe: d361f250684b8f5dd4073aa873971cb424959da7

000.exe: 33c341130bf9c93311001a6284692c86fec200ef

tunamor.exe: e398138686eedcd8ef9de5342025f7118e120cdf

stealer.exe: f839971b1fac2b0d6119b67440b90691b3d2bdc8

rniw.exe: 97bb45f4076083fca037eee15d001fd284e53e47

URLs/IPs:

hxxps://cdn.discordapp.com/attachments/884900935283916881/884913366945112094/exclude[.]bat

hxxps://cdn.discordapp.com/attachments/884900935283916881/884906713071890462/legion[.]exe

hxxps://cdn.discordapp.com/attachments/884900935283916881/884919522350477372/000[.]exe

hxxps://cdn.discordapp.com/attachments/884900935283916881/884919401500000286/tunamor[.]exe

hxxps://itroublvehacker[.]gq

162[.]159[.]134[.]233

What's Next for Protecting Open Source Ecosystems?

Just last year, my colleague and security researcher Ax Sharma had raised a question: "Will ransomware operators be the next threat actors to exploit trust within the open-source ecosystem?"

And, it seems he was right. While the threat actors successfully injected plenty of malicious executables, Trojans, and a simpler ransomware kit into a carefully picked typosquat, given the textual hints and the spooky video contained in the package, this incident appears more of a prank attack. But, it demonstrates the myriad possibilities that adversaries look at when targeting open source registries with clever typosquatting and dependency hijacking attacks.

October has been an eventful month in terms of malware repeatedly discovered on npm from the legitimate "ua-parser-js" library being hacked to dependency hijacking proof-of-concept (PoC) copycats Sonatype continues to catch daily.

This particular discovery is a further indication that adversaries aren't going to stop anytime soon. Sonatype has been tracing novel brandjacking, typosquatting, and cryptomining malware lurking in software repositories. We've also found critical vulnerabilities and next-gen supply-chain attacks, as well as copycat packages targeting well-known tech companies.

The good news is our automated malware detection system, powered by Sonatype Intelligence, has caught thousands of suspicious packages on npm - helping keep our customers safe. These components are either confirmed malicious, previously known to be malicious, or dependency confusion copycats.

Further, users of Sonatype's Sonatype Repository Firewall are protected from these suspicious packages while the review is underway. Existing components are quarantined before they are pulled "downstream" into a developer's open source build environment.

Sonatype's world-class security research data, combined with our automated malware detection technology, protects your developers, customers, and software supply chain from infections.

Tags